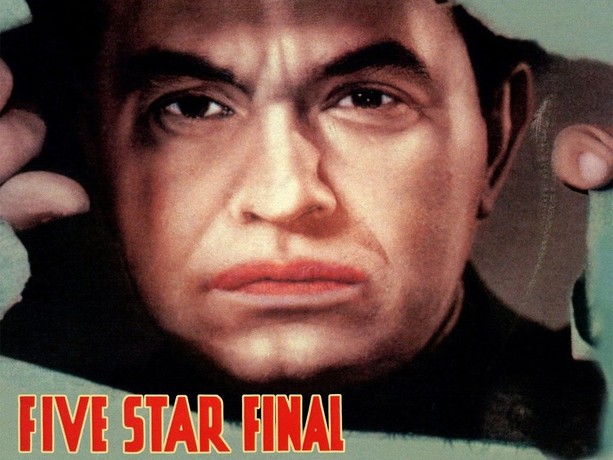

Rob Reiner’s Shock and Awe offers a dramatized but important retelling of how a small team of journalists at Knight Ridder questioned the U.S. government's push for war in Iraq in 2003. While most of the mainstream media blindly accepted the administration’s claims about weapons of mass destruction, Knight Ridder reporters stood almost alone in demanding evidence and challenging the official narrative. Their work represents a rare but vital moment in modern journalism when truth triumphed over popularity.

The film highlights a stark contrast between the behavior of the Knight Ridder journalists and many of their peers in larger news organizations. While reporters like Jonathan Landay and Warren Strobel questioned the intelligence being presented and sought alternative sources, major outlets like The New York Times and The Washington Post often acted more as amplifiers for the White House than as skeptical watchdogs. The press’s failure in the lead up to the Iraq War serves as a reminder of what can happen when journalists do not question authority.

Naturally, conflict arose between the press and the government during this pre war period. The Bush administration was determined to control the narrative, using fear and patriotism to build public support for military action. Any journalist who dared to push back risked being labeled unpatriotic or even accused of siding with America’s enemies. This placed reporters in a difficult position: do they tell the public what the government wants them to hear, or do they dig deeper for the truth, even at the cost of their reputation or career?

The Knight Ridder team faced not only government pressure but also resistance from within the media world. Their investigations was largely ignored or dismissed by other outlets and government officials alike. Despite publishing accurate and well-sourced story’s, they were treated like outsiders. This isolation only underscore the courage it took for them to stick to there journalistic principles when everyone else seemed to fall in line.

In today’s world, the Knight Ridder journalists should be viewed as hero’s not just by fellow journalist’s but also by the public. They upheld the values of truth, accountability and skepticism. Their actions serves as a benchmark for how the press should behave in a democracy; not as a mouthpiece for power but as a check on it.

Parallels to today are easy to find. In the age of misinformation, polarized politics, and social media driven narratives, the tension between the press and government continues. Whether it's issues of election integrity, public health, or foreign policy, journalists still face pressure to go along with dominant narratives. The lesson from Shock and Awe is that real journalism means asking tough questions, even when it’s unpopular.

While hindsight may be 20/20, it should not excuse the media's failures during the Iraq War. Instead, it should remind current and future journalists that skepticism, persistence, and courage are not optional they are essential. The press must learn from the past, or risk repeating it.